For photographers in Washington 90 years ago it was about access. Writers can listen or hear the story retold. For still and video photographers you’ve got to be there. Whatever the event or wherever it may be. This is the backbone of WHNPA’s history.

Today some refer to this access as transparency. We want transparency from our elected officials. And so it was … even in 1921! Ninety years ago, still photographers and newsreel cameramen in Washington probably didn’t call it transparency. They were just trying to do their jobs in making images of the president and others in official Washington. Up on Capitol Hill, the two things barred from the U.S. Capitol were dogs and photographers. Photographers didn’t even rate ahead of dogs.

News photographers with view cameras mounted on bulky wooden tripods and newsreel photographers with even larger movie cameras on even sturdier and heavier tripods waited on the street outside the White House. There was no pressroom. No White House “hard-pass” that allowed access onto the grounds. Enduring cold and snowy winters and notoriously hot and humid summers, these pioneering photographers waited outside the White House until they were asked to come onto the grounds.

News photographers with view cameras mounted on bulky wooden tripods and newsreel photographers with even larger movie cameras on even sturdier and heavier tripods waited on the street outside the White House. There was no pressroom. No White House “hard-pass” that allowed access onto the grounds. Enduring cold and snowy winters and notoriously hot and humid summers, these pioneering photographers waited outside the White House until they were asked to come onto the grounds.

There was no email list and no printed schedule for what the president was doing each day. Photographers would continue to wait outside in hopes of seeing someone who might have had an appointment with the president — and then hoping that person would walk past the cameras. And stop.

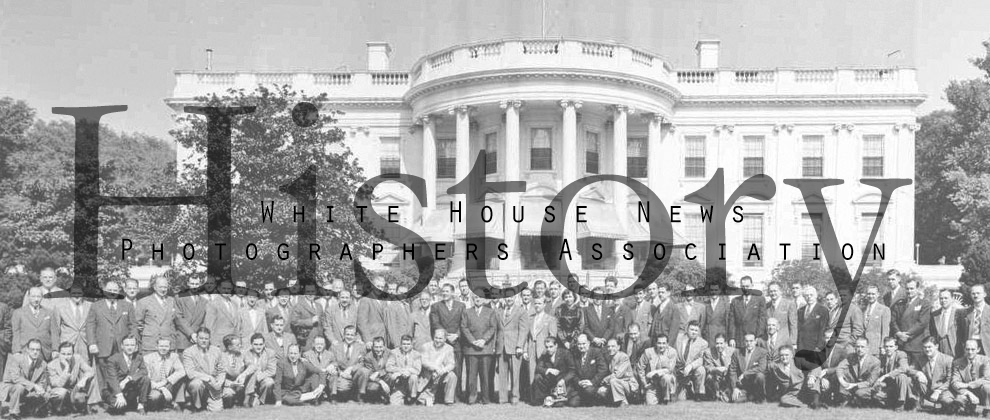

Broader access to the White House began for these photographers on June 13, 1921. On that date there were a grand total of 24 photographers working in Washington. These men formed the White House News Photographers Association and elected Arthur Leonard of Harris & Ewing as president, H.M. Van Tine of International News Photos as vice president and Joe Seligman of Harris & Ewing as secretary-treasurer. One of the founding principles — the protection and promotion of photographers’ interests in pursuing their mission — is as important today as when it was written into the bylaws in 1921.

Broader access to the White House began for these photographers on June 13, 1921. On that date there were a grand total of 24 photographers working in Washington. These men formed the White House News Photographers Association and elected Arthur Leonard of Harris & Ewing as president, H.M. Van Tine of International News Photos as vice president and Joe Seligman of Harris & Ewing as secretary-treasurer. One of the founding principles — the protection and promotion of photographers’ interests in pursuing their mission — is as important today as when it was written into the bylaws in 1921.

They got their access — at least to have the privilege of being invited inside. President Warren G. Harding set aside a room at the White House for them to use. The room was small and cramped, but it was inside. It wasn’t really until President Herbert Hoover that there was a formal press- room. Photographers started to find out about the meetings. They knew about the people the chief executive was to meet and could figure out why the meeting had significance — and, more importantly, if the images would be salable.

President Harding had been a newspaper publisher and seemed to understand why photographers needed access. Charter members of the WHNPA recalled him as a photogenic president who was photographed playing golf and horseback riding with visiting delegations. He was the first to have a widely photographed White House pet, a dog named Laddie Boy.

However, the members of the newly formed association still needed to “educate” their subjects on the value of news photos and newsreels. They were fighting against the way it had always been done when neither the public nor government officials cared about pictures. Too much publicity was vulgar. In any case, not enough mechanical and technical progress had been made to distribute images quickly. Quite often days or weeks passed before the public would see pictures from an event. The news was old by the time pictures reached outside Washington and around the world.

Photos were syndicated. Prints from those im- ages shot on glass plates were made and then sent through the mail or via train or plane to distant newspapers. Newsreels had to be duplicated, narrated and then sent to movie theaters by mail and train. There was no sound on the newsreels made in Washington until the early 1930s

Events certainly happened inside the White House, but photo- graphs were still taken outside — the South Lawn, the Rose Garden, even the Portico. Those cameras were still bulky and oh-so-slow. Long exposures, even outside. A 1/25 of a second would have been a blessing. No strobes that can keep up with the motors on the cameras of today. No lights that light up the inside event and balance it to daylight. Flash powder had been banned indoors because of the smoke and fire potential.

Events certainly happened inside the White House, but photo- graphs were still taken outside — the South Lawn, the Rose Garden, even the Portico. Those cameras were still bulky and oh-so-slow. Long exposures, even outside. A 1/25 of a second would have been a blessing. No strobes that can keep up with the motors on the cameras of today. No lights that light up the inside event and balance it to daylight. Flash powder had been banned indoors because of the smoke and fire potential.

For a late afternoon event in 1930, photogra- phers, for the first time at the White House, used flashbulbs. President Herbert Hoover was signing a $45 million drought relief bill and a $116 million public works bill. A story by the AP later reported that cameramen were using “a flash-lamp shaped like a giant electric light bulb. It blazed vividly,but there was no report, nor did smoke swirl as it did in days not so long ago.”

More competition in the news business meant more photogra- phers in Washington. Membership in the association grew steadily. Any photographer hired in Wash- ington became a member — at least if it was a ‘he.’ Women were denied membership until 1942.

Jackie Martin first applied for active membership on Aug. 5, 1929. She submitted another application on Dec. 4, 1941, and then finally on Feb. 27, 1942, was granted active membership. During World War II she became the official photographer for America’s first female army, the WAAC. By the end of December 1945, the associa- tion would boast five female active members.

Jackie Martin first applied for active membership on Aug. 5, 1929. She submitted another application on Dec. 4, 1941, and then finally on Feb. 27, 1942, was granted active membership. During World War II she became the official photographer for America’s first female army, the WAAC. By the end of December 1945, the associa- tion would boast five female active members.

However, it would take a question to President John F. Kennedy during an open press conference, before the first black photographer was accepted as an active member. WHNPA President Frank Cancellare knew that President Kennedy would not attend the annual “Eyes of History” awards dinner if this was not changed. There was a pending application from Maurice Sorrell and at the next general membership meeting, those few members who were using their vetoes — at the time a membership application could be denied by one veto — were on the hot seat to accept the application. Sorrell, a staff photographer for Johnson publications, became a longtime association member.

From the 24 photographers who formed the association 90 years ago, the WHNPA is now a vibrant organization with nearly 800 members. The struggle for access continues. President George W. Bush said at the 2005 WHNPA awards gala, “You might not remember what you read, but you will always remember what you saw.”

At its core, and regardless of the format — video, still or new media — our mission continues to be the “Eyes of History.”